Discussion & Learning — Rethinking Chengdu’s Identity through Food, Memory and Everyday Life

During the conversations that happened in the game-based process of Intervention 1, something unexpected emerged. Many participants described food as more than just eating. It immediately triggered memories of childhood, family gatherings, and a deep sense of belonging. For them, Chengdu’s identity is not rooted in official cultural symbols such as historical sites, heritage festivals, or government-promoted narratives, but in what Zukin calls everyday emotional experience (Zukin, 1995).

This insight challenged my original assumption that intangible heritage or “traditional culture” would be the dominant symbol of Chengdu. Instead, the most powerful expressions of identity seemed to come from lived experiences and the sensory memory of daily life.

To understand whether this pattern reflected something more universal, I began to compare participants’ views with existing literature and urban cultural narratives. Several key learnings became clear:

• Urban culture is not only built from heritage — but from everyday practices

Urban culture scholar Sharon Zukin argues that the identity of a city is shaped not by official culture or national symbols, but through everyday routines and ordinary practices performed repeatedly by people in the city (Zukin, 1995).

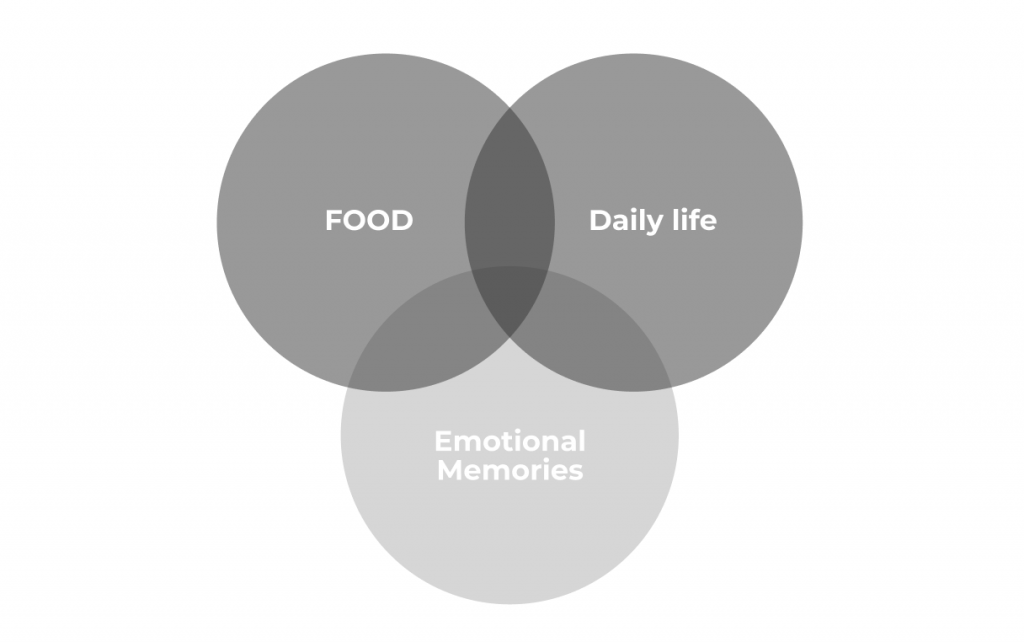

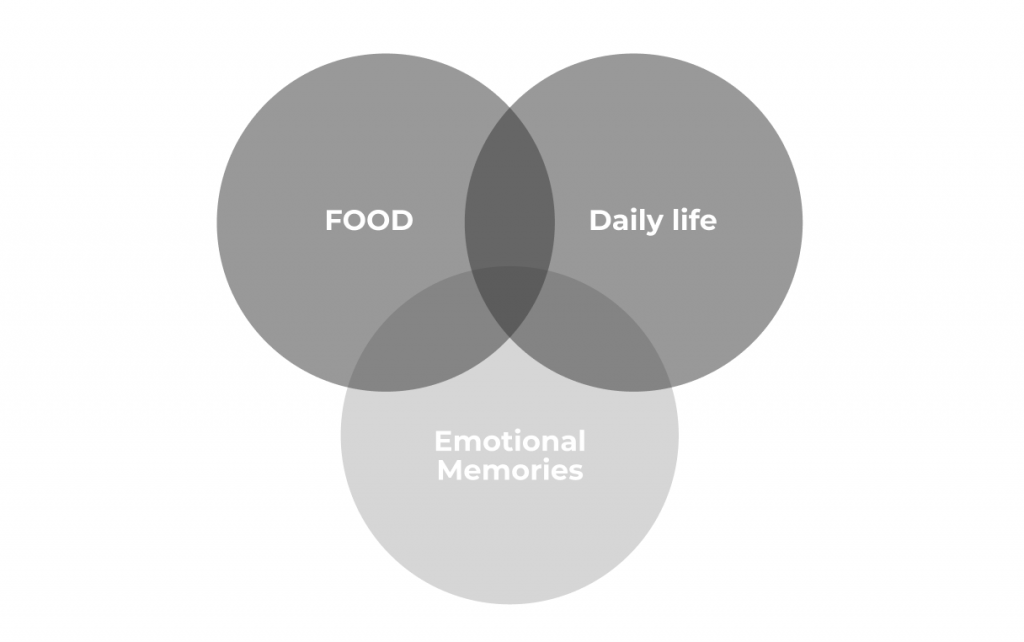

This matched perfectly with how participants talked about Chengdu. “Food + daily life + memory” became the combination that defined their emotional attachment to the city. It suggested that urban identity isn’t only created by museums, monuments or heritage—it is produced by everyday life itself (Zukin, 1995).

• Everyday Urbanism: where the meaning of the city is lived, not designed

Urban theorists working on “Everyday Urbanism” argue that cities are not shaped only by grand planning or official culture, but by markets, teahouses, alleyways, street food, and neighborhood interactions (Crawford, Chase & Kaliski, 1999).

These ordinary spaces make the city feel alive and embodied. And when I looked at Chengdu through this lens, I realised how naturally participants linked food, lifestyle, and memory with their sense of belonging (Crawford et al., 1999).

• Urban identity is not fixed— it is constantly produced and reproduced

Urban identity is not an essential or stable concept. It is produced through interaction among different groups of people—locals, migrants, tourists. Through shared spaces and lived experiences (Lombard, 2014). In other words, identity is always in the making, not a finished product.

This is exactly why bringing together Mixed and Local groups became so meaningful. The conversations acted like a small social experiment that revealed how Chengdu’s identity is constantly negotiated, reshaped, and reproduced (Crawford et al., 1999; Zukin, 1995). Their different viewpoints didn’t conflict—rather, they co-created a richer definition of the city.

What I learned is that the real meaning of Chengdu doesn’t only exist in official cultural language. It exists in the everyday and in the emotional. In the food we share, the places we return to, the memories we carry with us.

Reference

Crawford, M., Chase, J. and Kaliski, J. (1999) Everyday Urbanism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Lombard, M. (2014) ‘Constructing ordinary places: Place-making in urban informal settlements in Mexico’, Progress in Planning, 94, pp. 1–53.

Zukin, S. (1995) The Cultures of Cities. Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Chinese Version:

Discussion & Learning — 对比访谈与文献/城市文化叙事

在此次 Intervention 1 的 Mixed group 与 Local group 的游戏过程中的谈论了解到,许多参与者都强调“食物”这一日常体验对他们而言不仅仅是简单的消费或饱腹行为,而是唤醒童年、家庭以及归属感。对他们而言,成都的城市身份认同 (urban identity / sense of place) 并不来源于官方文化符号 (如历史景点、传统节日或政府推广的非物质文化遗产),而是everyday emotional experience(Zukin, 1995)。这一发现令人惊讶,也与我最初假设的“非遗 / 静态传统 = 城市文化核心象征”的预期不符。

为了验证这种发现是否具有普遍性或理论支撑,我将访谈结果与现有学术研究和城市文化叙事进行了对比。以下是我的几个主要学习点 (learnings):

• 城市文化不应局限于官方 “文化资产”,而更植根于日常实践

在经典城市文化研究中,Zukin (1995) 指出urban culture并不等同于民族、种族或传统文化,也并非完全由审美或官方文化塑造,而是通过人们在城市中不断重复的日常实践而生成(Zukin, 1995)。

这与我访谈中参与者强调“食物=童年/家庭/记忆/情感”的观点高度契合。“食物 + 日常生活 + 情感记忆”的组合构成了他们对成都这座城市的认同。这说明城市文化不应只依赖于“官方文化符号”,而是应回到日常生活实践本身(Zukin, 1995)。

• “Everyday Urbanism” 的视角:将城市意义还给平凡生活

在城市研究与规划理论中,“Everyday Urbanism” 强调城市不是由宏大规划或官方文化机构定义,而是由普通居民、街头、市场、饮食文化、邻里互动所塑造(Crawford, Chase & Kaliski, 1999)。正是这些可触及、可感知的日常空间使城市被生活化并具有情感意义(Crawford et al., 1999)。

• 城市 identity 是被持续生产的过程,而非固定属性

在城市社会学研究中,有学者指出城市身份是通过居民、迁移者与游客在日常实践中的互动与再生产不断形成的,而非一次性被定义(Lombard, 2014)。也就是说,城市文化本身就是一个被不断讨论、塑造、争夺与重构的社会过程(Lombard, 2014)。

而 Mixed / Local 分组正是揭示这一“城市身份生产机制”的实验结构,它通过差异化的文化视角迫使参与者重新界定成都的意义,实现了一种社会化与互动性的文化再生产(Crawford et al., 1999; Zukin, 1995)。

Leave a Reply