In the second-round intervention, the most significant outcome was not the identification of three representative foods, but the process through which participants shifted from personal preferences to collectively abstracting the criteria for “Chengdu-ness.”

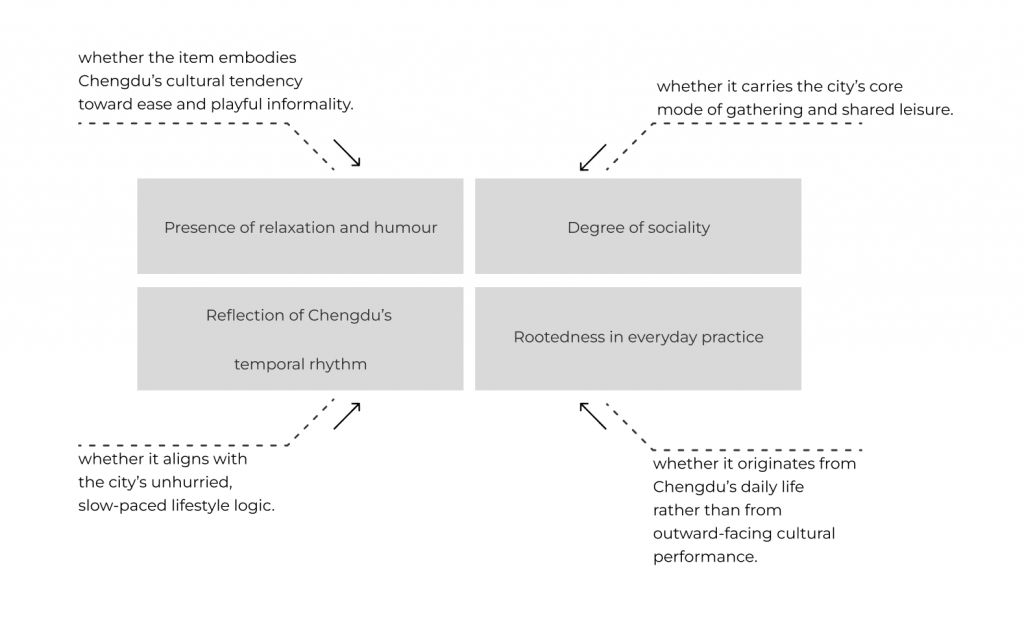

At the beginning, participants selected foods based on subjective reasons such as “I like this” or “I grew up eating this.” However, during rounds of debate and mutual questioning, they realised that personal taste alone cannot justify why a food represents Chengdu. As the discussion deepened, participants began to articulate structural qualities that distinguish Chengdu from other cities. Through this iterative comparison, four criteria gradually emerged:

These criteria were not pre-designed by the researcher; they were co-constructed as participants moved through a cycle of questioning, comparing, and redefining meanings. This process demonstrates how cultural identity is dynamically generated through interaction, a phenomenon consistent with Bourdieu’s (1984) notion of identity formation through everyday practice.

Thus, the real methodological value of the second intervention lies not in determining which foods represent Chengdu, but in establishing a cultural selection mechanism that can evaluate what counts as culturally representative.

Reference

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chinese Version

在第二轮干预中,最关键的成果并非找出哪三种食物能够代表成都,而是参与者在讨论中 从个人偏好逐渐转向共同建构“成都性”判断标准的过程。

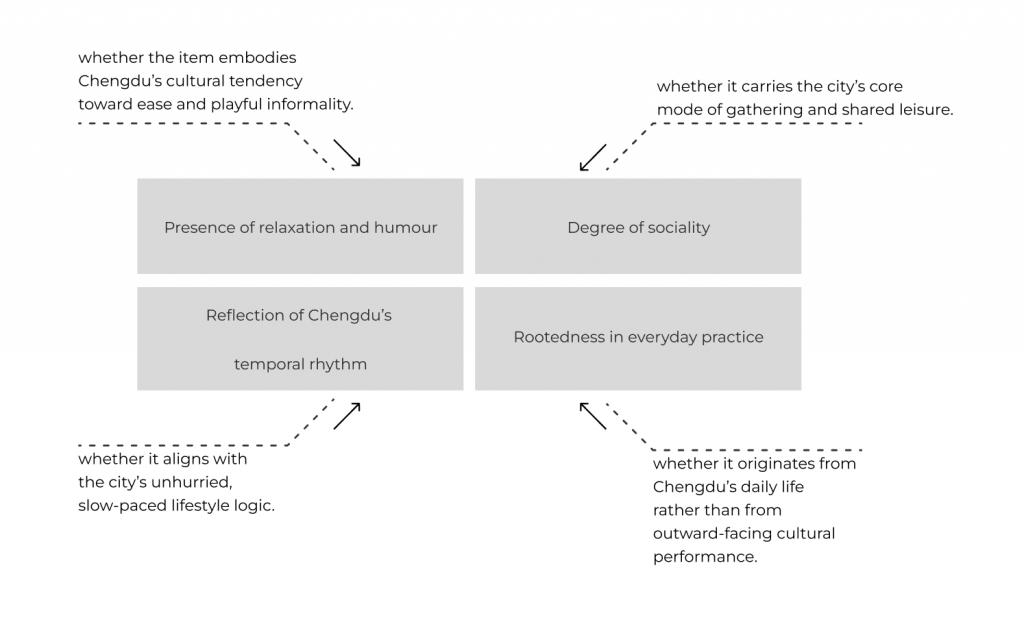

讨论初期,参与者基于“我喜欢”“我从小吃这个”等主观理由进行选择。然而,随着反复质疑与互相比较,他们意识到个人口味无法解释一种食物为何能够代表成都。随着讨论深化,参与者开始抽提出区别成都与其他城市的结构性特征。通过不断比对,他们逐渐形成了四条文化筛选标准:

这些标准并非由研究者预设,而是在参与者的不断提问、比较与意义重构中 共同生成 的。此过程体现了文化身份在互动中被动态建构的机制,与 Bourdieu(1984)关于“身份由日常实践生成”的观点一致。

因此,本轮干预真正的方法论价值在于建立了一个文化筛选机制,用以判断何种文化元素能够代表成都。

Leave a Reply